Why do I Make Films?

By Apo Torosyan

June 2008

In the beginning, it was drawing on paper. The magic of creating something. An image on a virgin surface, susceptible to any experimentation. Then, it was texture, the time element, which got on canvas and paper. It was my environment, the 3,000-year-old city of Istanbul, Constantinople, capital city of two empires. The aged walls, deteriorated frescoes and mosaics, the signatures of humanity.

I carried all of these influences with me and brought them to my new world in 1968. Coming from the very old to the fairly new city of Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. What I had with me was my identity. What was surrounding me was the new world order comparing chaos, old traditions facing new traditions, old knowledge facing new knowledge. It was a new identity river with the power to engulf my old identity. After adjustments and struggle, I realized I was accepted with a mixture of my old and new identity.

My first step in creativity was my own identity as a family man and provider. I chose to create my own company. Within two years I had a visual design company and I was freelancing on the side. Within 4-5 years I was full-time in my career and I was training people to work in my corporation. Within 18 years I had a national and international business to sell to a competitor. This was my first career in the United States.

By 1987, I was totally dedicated to my art, which I had neglected for all of these years. The fever of creativity was the same. I started on paper, and created 300 works in one year. Then, I had the courage to work on canvas. I was running full speed, like a hungry man in a banquet. Experimenting, testing, destroying to rebuild. Challenging the past and the future. What a privilege that was. It was like an odyssey, lost, looking for the new. I always believe that what I was looking for was within my reach, but where?

Then, I remembered my art professor Bedri Rahmi Eyuboglu’s advice: “Whatever you do, make sure it is yours.” That was it- but what was mine? Texture- yes, I came from a deeply textured world- the time element- and I could see that I was surrounded with it even in the new world.

What else was mine? My roots, my family history? Starving family members dying during the Armenian, Greek and Assyrian Genocide, including my grandparents? My father looking for food in the garbage cans at five years old? My uncle digging his own grave with other young Armenian men from the villages? Surviving to tell us his horror story, to tell us and the world? Yes! I could tell those stories. They were related to bread as a metaphor.

The bread, which was the staff of life, was taken away from my ancestors. It represented victims of oppression. They died in starvation. I immortalized the bread within my concepts. It was an organic metaphor. It was the cycle of life.

So, how could I use this material, the bread? And, of course, the earth, the “Immigration” installation that renewed itself by participation of the visitors. Would the bread in my artworks survive the elements? Would it be ridiculed? How could I put this story into an esthetic frame? How could I introduce to this new world the old world’s forgotten story? How could I have the visitors to the exhibit participate in the show? How could I make the exhibit renew itself every day?

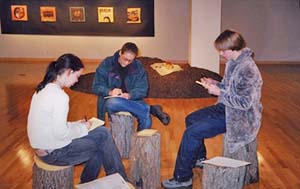

Those were the challenges of the “Bread Series” and “Immigration” installation. The “Immigration” installation used large mounds of earth around the exhibition floor, with the “Bread Series” mixed media paintings on the walls. Newspapers from different countries lay on top of the earth mounds with loaves of bread, and a soundtrack had the sound of bare hands making dough.

Once, while I was setting up the installation at a college, a student passed by and asked me “Why dirt?” I said, “That’s not dirt.” He said, “What is it?” I said, “That’s you.” He took a step back and said, “Am I dirt?” and I said, “Of course not. This is earth. That is where you came from, and when you are done with your life, that is what you are going to be.” I could see the change of vision on his face. This was my second career, almost another 16 years, 1987-2003. This brought me to my new career, filmmaking.

It started in 2003, when the Forum on Tolerance from the North Shore of Boston asked me to make a presentation on the Armenian Genocide. This was the incentive for me to go a buy a new mini digital video camera, learn how to use it (with the help of a filmmaker friend) and visited my father’s village, Edincik in Turkey. I recorded the film in Edincik in September 2003, came back from Turkey and finished the film in October, and presented it for the first time at the Forum on Tolerance at North Shore Community College in November 2003.

I remember the full audience at the auditorium of the College in the city of Lynn, Massachusetts. The audience filled all the seats and the side bleachers. North Shore newspapers had publicized the event, so I had a good coverage. Faculty members, friends, relatives, students and other audience members crowded the room, young and old, in every garb and tradition, waiting for my talk to begin.

Then I felt that cold chill on the back of my spine. It was the same chill that I had faced in the middle of a cold winter night, looking down the barrel of a loaded gun, with the trigger pulled by the officer. It was in Istanbul a long time ago. This time, at North Shore Community College, I knew that every word I would speak about how my family (partially) survived the Armenian Genocide was like a nail in my coffin of freedom of speech in Turkey. I knew that, as this was the first time I was speaking in public about this taboo (for Turkey) subject, the doors were closing to my face. I knew I was never going to see my city, Istanbul, and the country where I was born. I knew all of my Turkish friends in America were not going to talk to me, not invite us to their homes or weddings. All of these things that I foresaw in that brief moment came true.

It was a few weeks ago (May 2008) that I had a meeting with a copyrights lawyer in the Boston area. His office was right across from my old Turkish friend’s shop. So, after the meeting with the lawyer, I crossed the street and walked over to my friend’s shop. His son was working in the back room. We hugged and kissed in the Middle Eastern tradition. I told him that I had missed them all. I asked about his children, and was happy to hear that they were grown to his height (6 feet tall) and playing basketball. When I had last seen them, they were only 36” tall.

Then, his father walked in, again hugs, but he was distant. We talked about our grandchildren. With pride and joy I told him about my two grandsons, and my upcoming granddaughter in the summer of 2008. Then the son asked what I was doing in that area. I told him that I was making films now, and he asked “What films?” I said, “Some of the films are about what happened to my family and the Armenian Genocide, and since I have started making these films and presentations about the Genocide, your parents and the old Turkish group is not talking to me.” The father by now was trembling all over. He started accusing me of getting paid by Armenians in this country to make my films.

I told him I wish I was, but I was making these films with my own funds. He kept giving me the typical Turkish denial rhetoric, and I told him I had come to visit them with love and nostalgia, not hate. When I left he was angry at me and still shaking all over. His son was more quiet. On my way out, I told the son to look into history without Turkish sources, and left with well-wishes from my side to the old Turkish friends group.

By now, you have probably figured out why I have started making my films, which are not all related to human rights, but to life itself. I never realized the power of a DVD compared with the power of an art exhibition, even if it was in a museum. My documentaries have been shown in places that I have never been, and have been seen by thousands and thousands of people whom I have never met. And through the Internet I have met a lot of new friends with the same message “Hope not Hate.” |